|

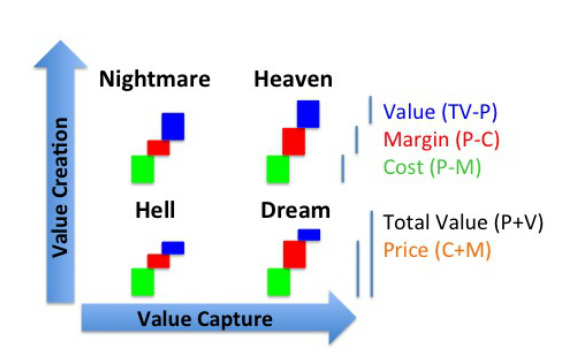

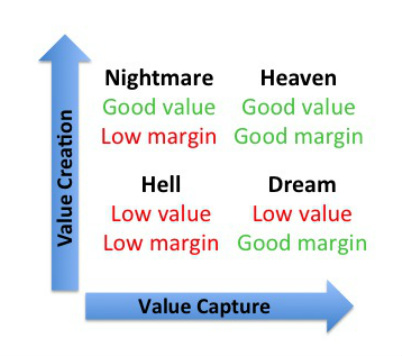

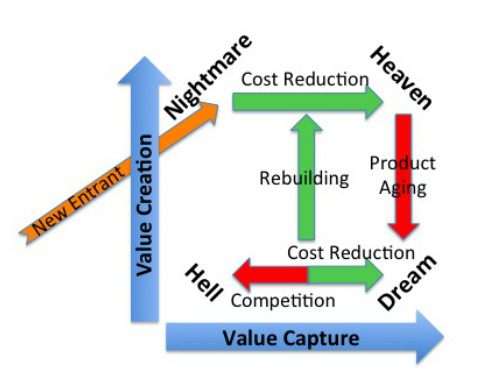

I really like the business term “to appropriate value,” which means to secure or collect on the value of something. Appropriating business value is generally broken down into two sequential steps: value creation and value capture which correspond to product (or service) development followed by marketing and sales. I recently came across an interesting construct from Professor Paul Verdin of Solvay, KUL and INSEAD and his colleagues on the web (click here and here). In this construct, termed the VC2 Matrix, value creation and value capture are shown on separate axis (redrawn below). Products in each of the resulting four quadrants can be described in terms of the relationship between their cost, margin (or price) and net (or total) value to the customer. For example, if value creation is high but value capture is low, the result which they term “Nightmare” is a product with significant value to the customer but which generates only low margins. This inability to capture strong margins could be a result of high costs and/or strong price competition. The high cost scenario is often the position early-stage companies and new products find themselves in before economies of scale can be realized. As for all models, we can only appropriate their value (pun intended) if they inform our future actions. Here too Prof. Verdin et al. outline strategies to move products from the three unfavourable positions to “Heaven,” through building additional value and/or cost cutting. They also describes how products can fall from “Heaven” and move to “Hell,” through the competition eroding added-value and prices. The three available levers are your cost structure, pricing strategy and customer value. Improving your cost structure can involve economies of scale, outsourcing, building for manufacturability (and service), improving productivity and automation. Improving your value proposition involves differentiation, including through new offerings, service, quality, bundling of products and services, and patent protection. Your pricing strategy and the resulting margins are squeezed between and are highly dependent on the other two levers, as well as the competitive response. A combination of advertising, branding, reputation, promotions, loyalty programs, lock-ins, convenience, and financing can be applied to differentiate on price alone.

© Duncan Jones (2013) All rights reserved

0 Comments

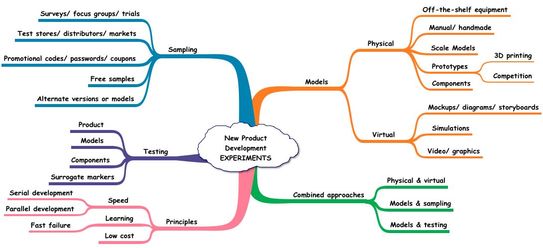

“Test fast, fail fast, adjust fast” Tom Peters Many unknowns are encountered during the development and commercialization of new growth strategies, new product categories, services or business models. In order to improve one’s knowledge, decision-making, and probability of success as well as mitigate the risks within this “fuzzy front end,” thorough, thoughtful and frequent experimentation is critical. Tom Peters eloquently highlights the importance of testing, speed, and learning to drive the process. We would add seeking means to manage/ minimize the costs as well as performing parallel testing to round out these principles. Based on these principles, a brief review is presented on some of the potential experimental approaches involving models, tests and sampling of customers as well as the value of combining these approaches. Scale models and prototypes are an obvious place to start. With the advent of 3D printing, in many cases they are becoming faster and more cost effective to produce. A model allows one to really see and understand the product and in many cases can be used for testing. The rough assembly of off-the-shelf equipment is another quick and less costly means to develop a testbed. We worked on a breast cancer screening procedure/ device that was initially constructed from modified ECG equipment and manual measurements. Computer graphics and simulations can be used to demonstrate the look and functionality of products before they are built. This is of course common in the automobile and airline industries and becoming popular with home renovators. In addition, non or partially functioning mockups of applications can be quickly designed to demonstrate the user interface and future functionality. This is a very common approach used to flush out the specifications for smartphone apps. Finally process flowcharts and simulations are often a valuable contribution to understanding how a new product or service will be made and/or used and to identify potential issues early on.

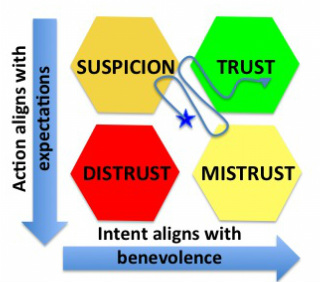

Having developed physical or virtual models or even a first version of the product, these or the key components can then undergo testing. Physical tests and examinations might include functionality, ruggedness, aerodynamics, ease of assembly and service, and means to reduce the number or complexity of the parts. We once built a mocked-up office to test a power wheelchair’s maneuverability. For virtual models and mockups, many of these same physical tests can be computer simulated including aerodynamics, spatial constraints and assembly. Obtaining potential customer and expert opinions through sampling is another important part of the new product development process. This can be carried out using many of the techniques marketers employ: focus groups, trials, samples and promotions in order to collect valuable feedback. It is not necessary to have a fully functional product to solicit opinions. The parallel testing of different models simultaneously (with the same or different individuals) can save significant time although there is a tradeoff with cost. Combining multiple experimental approaches can be very powerful. We have already touched on how many models, especially larger and later stage ones can go on to extensive testing and various forms of sampling. In addition models that combine physical and virtual components can be developed. Our second generation breast cancer screening device involved custom built electronics controlled by a personal computer, prior to the final fully-integrated device. By developing a list of questions around the unknowns of your new product development and then brainstorming as to which models, tests and sampling can get you the answers in the fastest and cheapest manner, will allow you to learn and make the necessary modifications along the way. Too many entrepreneurs believe they have the “answer” and forge ahead to the final product with minimal experimentation, only to find it is not a satisfactory solution. “It is possible to fly without motors, but not without knowledge and skill.” Wilbur Wright © Duncan Jones 2013 All rights reserved I recently watched a 2012 TEDx University of Waterloo talk entitled “Who can you trust?” My friend and colleague, Andrew Maxwell, who is an Assistant Professor of Strategic Management at Temple University in Philadelphia, gave it and I highly recommended it. It can be found on YouTube at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1mAFFtVV5B4&feature=share&list=SPsRNoUx8w3rM27gSBuijVfTpFGKtGOhDD. In his talk, he present a diagram, redrawn here, that got me thinking about my days as a venture capitalist and how trust - or the lack of - influenced our investment selections. Key:

Trust: Firm belief in the reliability, truth, ability, or strength of someone or something. No reason to take action to alter the process. Suspicion: Feeling or belief that something is wrong or someone is being dishonest but without enough evidence to take immediate action. Mistrust: Lack of or damaged trust or confidence that can take significant time to repair, often through the provision of additional information or assurances. Distrust: Regard as wrong or dishonest with a deliberate intention to deceive or violate trust resulting in immediate avoidance and exclusion. Before hearing a pitch an opportunity or reviewing a plan, VC’s are neutral. As indicated by the arrow in the diagram, as we learn more we experience periods of suspicion and even bouts of mistrust but if we can work through these we can get to trust, make a deal/ investment and become partners moving forward. If too much mistrust builds up, the deal reaches a point of being too much trouble to bother with. On the other hand, if even the slightest bit of distrust develops the deal is dead. A well constructed, detailed, written business plan can help build trust, allay suspicion, minimize mistrust, and prevent any deal-killing distrust from arising. It achieves this in two ways: The document itself demonstrates that the entrepreneurs have thought-through the opportunity and carried out enough supporting research. Of course, not every issue or contingency can be addressed, as this is the “fuzzy front end” of new product (or service) development. However, it is important to demonstrate that all the major issues and risks have been carefully considered and addressed as best as possible. Even more importantly, the document serves to keep the entrepreneurs on point. When faced with tough and penetrating questions from investors, ill-prepared entrepreneurs often try to bluff their way through. This usually leads to suspicions or mistrust, which frequently evolve into distrust and the end of any fruitful relationship. On the other hand, well-prepared entrepreneurs build trust by demonstrating they have considered the vast majority of the issues and can offer approaches to resolve them. Additionally, their preparation gives them the confidence to say, “We haven’t considered that, but will look into it and get back to you” when a novel question is posed, minimizing any further suspicion, mistrust or distrust. New business opportunities require entrepreneurs and investors to come together as partners. These relationships require trust. Trust that the opportunity and risks are what the entrepreneurs say they are, trust that the entrepreneurs will execute the plans to the best of their ability, and trust that entrepreneurs will keep communications open. By making the extra effort to prepare a well constructed, detailed, written business plan, entrepreneurs can go a long way to building this critical trust. © Duncan Jones 2013 All rights reserved

“Strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory. Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat.” Sun Tzu, The Art of War

“Create something, sell it, make it better, sell it some more and then create something that obsoletes what you used to make.” Guy Kawasaki “Written goals provide clarity. By documenting your dreams, you must think about the process of achieving them.” Gary Ryan Blair A recent article in the Harvard Business Review (May 2013), “Why the Lean Startup Changes Everything” by Steve Blank got my attention. He argues that you should “sketch out your hypothesis” (using the excellent Business Model Canvas[1]) and get going right away. Under the heading of “The Fallacy of the Perfect Business Plan”, he states, “According to conventional wisdom, the first thing every founder must do is create a business plan … A business plan is essentially a research exercise written in isolation at a desk … The assumption is that it’s possible to figure out most of the unknowns in advance.” No doubt the author wrote this as somewhat of an exaggeration, as a stark contrast to make the case for a quick, iterative, customer-centric design and build approach, that clearly sounds more exciting, efficient and on point. This methodology is sometimes referred to as customer development. He then goes on to present a more detailed model adapted from the iterative and incremental Agile software development methodology that has recently been espoused over the classic, linear waterfall method[2]. While I certainly agree with the need to get going and not get caught up in the paralysis of analysis (as would Guy Kawasaki quoted above), the need for planning and writing it down is equally important (here Sun Tzu and Gary Ryan Blair seem to agree). Indeed in Steve Blanks’ model each iterative cycle starts with planning followed by requirements, and analysis and design prior to implementation, testing, and evaluation. Sounds like business planning to me! Like most things, the answer lies in the middle. I recommend to every entrepreneur that they do fairly extensive planning and put it down on paper[3]. I do not however recommend that this planning be done as a “research exercise written in isolation.” The greatest value in developing a business plan is forcing you to list your assumptions. The more detailed and explicit the plan, the more explicit will be the assumptions and the easier it will be to identify inconsistencies, problems and additional opportunities[4]. These assumptions and especially their interrelations can then be subject to testing in a prioritized manner now or as the opportunity matures, whether that be by desk-based internet research, by talking with suppliers, customers, industry experts and opinion leaders, by creative thinking and debating among your team, and/or testing in the market/ customer development[5]. A plan that I recently assisted with included an appendix of over 120 frequently asked questions (FAQS) as seen on many websites[6]. This proved to be a great opportunity to use the invaluable question and answer format to further probe all of the assumptions and possible issues not made quite as explicitly in the core 35-page plan. Aside from some delay, two other arguments against writing a business plan are: that it is a lot of work, and that it will never be correct so it’s of little value. This is also the reason that many plans become a static document collecting dust on some shelf. Indeed, it is labour intensive and the reality never turns out as planned[7]. However as discussed previously it’s the process that is as, if not more, important then the resulting plan. For the early-stage companies I worked in or very closely with, I carried around a bound copy of the plan, referring to it frequently and making copious notes in pencil in the margins as I learned new things and revised the assumptions. When the weight of plan had increased by 8 gm (the weight of 1 pencil lead), I knew it was time to redraft it and did so![8] These business plans became living documents with our assumptions kept both top-of-mind and as accurate and up-to-date as possible. On the other hand, proceeding without much planning increases the risks and can lead to serious setbacks. Perhaps the most damaging being having your opportunity turned down by potential investors. You’d be surprised how many entrepreneurs I have met with new, breakthrough ideas that I find already exist on the market within a few minutes of Googling. More common problems are misunderstanding customer needs, the actual market and its size, and the intellectual property landscape, as well as underestimating regulatory concerns, sales cycles, competitors and competitive products, costs, and of course the time required to complete various activities. Rushing into an opportunity is rife with dangers, as is planning to perfection. The right approach is a balance. This involves combining detailed and iterative planning with research, and field-testing and experimentation. In doing so, you can move your opportunity forward towards commercial success as effectively and efficiently as possible. © Duncan Jones @Hexagon-Innovating.com 2013, All Rights Reserved. Endnotes: [1] Business Model Generation (2010) by Ostewalder and Pigneur as well as 470 practitioners. This is a great book both in content and design. Their, now famous ,9 building blocks and the associated graphic are now seen everywhere (see www.businessmodelgeneration.com) and are extremely valuable for planning or analyzing an opportunity. The design of the book is also fantastic: very visual, well laid-out and fun. A must buy at about $40. [2] Coined in 2001, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agile_software_development [3] My consulting practice involves helping entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs enhance their strategic innovation efforts, through better planning, researching and experimentation. See www.hexagon-Innovating.com for more details. [4] Some of my favourite inconsistencies and assumptions include: Huge sales forecasts with no or very little marketing budget - “It will sell itself.” The belief that the product or service is so unique that either there is no competition at all (and never will be) or if there are “distant” competitors they will not (never) respond to your market entry. That the market penetration will reach 90-100% of the target population whereas Google search has an 89% share, Android OS 55%, Samsung TV’s 28%, Sanyo batteries 23%, Rolex luxury watches 22%, McDonalds 19%, General Motors 12%. [5] Using your network of colleagues or their network indirectly through referral or LinkedIn is a valuable tool. I have found that most people are very willing to provide advice or share their knowledge as long as you have done your homework and are asking good, well though out questions. That old device the telephone works well, sometimes a coffee or lunch is more effective, and of course there are many opportunities at conferences and trade shows. [6] Given the importance of understanding and getting a feel for the assumptions and their interrelations, I believe that the founders should hold the pen and do most of the business planning and writing. When I was a VC, I never funded a plan, (at least obviously) written by a 3rd party! Consultants and other advisors can provide valuable input reviewing, questioning and providing advice and in some cases doing sub-tasks like competitive intelligence research. In fact going a step further, I believe every team member should build their own simple financial model based on the core model as this is the best way to get a feeling as how all the parts come together and their sensitivity to minor changes. I have always done this whether assisting firms or conducting due diligence. [7] A standard venture capital rule of thumb is that plans always take twice as long and cost twice as much to execute. To sound more scientific, we often used π (pi or 3.1415926536) instead of 2! [8] We never did weigh the plan (actually measure its mass to be perfectly correct) instead we could tell by the quantity and importance of the scribbles. {The mass of a pencil lead, which is actually graphite and clay, was estimated for a 2 mm diameter lead, 130mm long with a density of 2 gm/ cm3}. |

AuthorDuncan Jones Archives

June 2024

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed