|

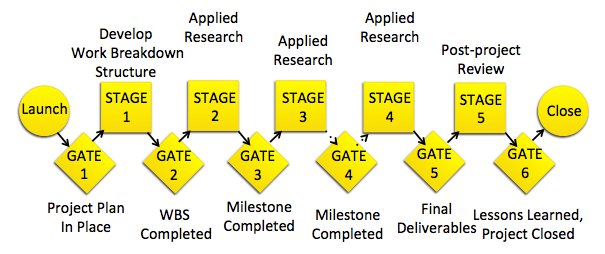

Killing/ cancelling projects in the face of more promising opportunities is very difficult. Projects can seem to take on a life of their own. All of the stakeholders involved in the project, from the project team, senior management serving as the project champion, possibly investors, and even interested potential customers can become invested in the project - a combination of passion and desire to push on, belonging, familiarity and comfort, buy-in, and not wanting to acknowledge failure or realize a financial loss. Nevertheless some projects, that despite good initial intentions, are unlikely to achieve their goals for any number of strategic, technical, commercial, financial or operational issues. Cancelling a project frees up human and capital resources that can then be redeployed on more promising new or existing projects. In doing so, a firm can retain a robust portfolio of projects and improve the overall innovation probability of success. A effective way to oversee a single project or number of projects in a portfolio, to ensure that efforts and resources are driving innovation, is to implement a stage-gate (or phase-gate) process. A stage is a task or series of tasks that are focused on achieving an important and measurable sub-goal of the entire project (also known as a milestone). Examples include building a working prototype, receiving regulatory approvals, raising financing, or product or service launch. Each stage is generally associated with a budget and a timeline for completion. A gate, as the word implies, is a moveable barrier. This is where a project stops to be re-evaluated based on completion of or failure to complete the current stage and reach the milestone. As part of this re-evaluation, the continuing relevance of the overall project’s goals are also examined. Each gate thus serves as a Go/No-Go (or Kill) decision point based on a pre-defined set of criteria. Projects receiving a Go pass through the gate and move on to their next stage. Having pre-established gates and detailed Go/No-Go minimal criteria for each stage are critical. Without these, the process loses its objectivity. The minimal acceptable criteria should incorporate the four components of a project namely scope, quality, time and cost. The scope being the detailed set of deliverables or features, derived from a project's requirements. It is also defined by the Project Management Institute as "the work that needs to be accomplished to deliver a product, service, or result with the specified features and functions.” The gate for developing a functional prototype of a new bicycle might include the following criteria: The bicycle is to incorporate the new frame design, to weight no more than 12 kg, to support a 100 kg rider, to contain all the standard components, and to withstand forces of 3 kN at each joint. Colour and frame graphics are not required at this stage. (Scope and Quality). This functional prototype should be delivered by January so that full production can commence on schedule at a cost of $1.0 million including a 10% contingency (Time and Cost). A gate for a market research project might include: Survey at least 100 personal trainers and confidentially collect information on their hours worked, their hourly pay and their top three issues. It is expected that client injuries will be mentioned as a top issue by more than half the respondents to justify our proposed solution (Scope and Quality). This stage is scheduled for one month at a cost of $10,000 (Time and Cost). These four project components (often referred to as constraints) are interrelated. A formula that captures the tradeoffs is Quality x Scope = Time x Cost. This illustrates that to deliver a certain product or service with acceptable quality requires a certain combination of time and money. Of course, it also implies that with enough time and money almost anything is possible, and the more practical corollary that time and/or budget constraints will negatively effect either the scope or quality of the outputs or both. In evaluating projects against minimally acceptable criteria, scope and quality should not be compromised whereas there may be some flexibility in time depending on market conditions. The constraint best able to absorb difficulties is cost: Putting more resources on a project to ensure it comes in with the desired scope and quality, and within an acceptable timeframe is usually worthwhile as long as those additional costs are “reasonable.” As outlined above, gates can be established at any major milestone. However, some practitioners prefer to use the traditional process for every project involving five fixed stages and gates as follows:

As these traditional gates are indeed major milestones, adding some additional gates to this list especially within Stages 3 and 4 for larger projects is highly recommended. If project management tools are being used, as they should be, the work breakdown structure and resulting Gantt chart can be of great value in establishing and identifying key milestones where gates should be incorporated, based on the difficulties and the risks ahead. The value of the Stage-Gate process is six-fold:

Not having a formal stage-gate process can result in work being carried out on too many projects including marginal projects. As a result, many of these projects will not deliver significant value in a timely and cost-effective manner while commanding resources that could be more effectively employed elsewhere. However, a formal process can swing the pendulum the other way, cancelling too many projects that don’t meet the precise, current gate criteria. Therefore, it is important in cases where the criteria has not quite been met for the review team to explore the root cause(s) and explore means to achieve these sub-goals in the near term. This could involve extending the timeframe, providing additional resources, doing some additional experiments to clarify the path forward, or exploring an alternate path. In effect, taking a positive approach and be open to providing a second chance. That is not to say that in many cases the outstanding hurdles will be too difficult, take too long or be too expensive such that project cancellation is indeed the correct decision. In fact, projects are unique and risky undertakings and so some failures resulting from a lack of feasibility or changing market conditions can and should be expected. A decision to cancel a project can take place on two levels: the project level and the portfolio level. At the project level, the decision should focus solely on the project and its pre-established criteria. These meetings should be scheduled based on the established gates or in rare cases: extraordinary and material events. As each project develops at its own pace, these meetings will unlikely involve other projects simultaneously. In fact, the best project cancellation decisions arise as a recommendation from the project team who has come across an issue, explored all the options and have concluded that the potential business case or value no longer justifies ongoing efforts. Portfolio decisions to cancel or at least significantly scale back projects are necessary to strategically reallocate scare resources and hence involve all of the projects currently in progress or being planned. Such portfolio decisions should not be taken lightly. As a result, they require a separate meeting, set of procedures, and usually a different and broader group of decision-makers. These meetings are usually held on a scheduled quarterly, semi-annual or annual basis in conjunction with budget reviews. Nevertheless, portfolio decisions also rely on the business case, project plan and the progress against the stage-gates of each project. Cancelling projects, although critical to long-term success, can be taxing on an organization. In order to minimize the adverse effects, it is recommended that four procedures be put in place:

The stage-gate process can be a valuable tool to manage just one or a portfolio of projects. Its primary value is improving awareness and communication which are critical for better decision-making. “Stage-Gate Process” by Duncan Jones, Hexagon Innovating (2016) is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

2 Comments

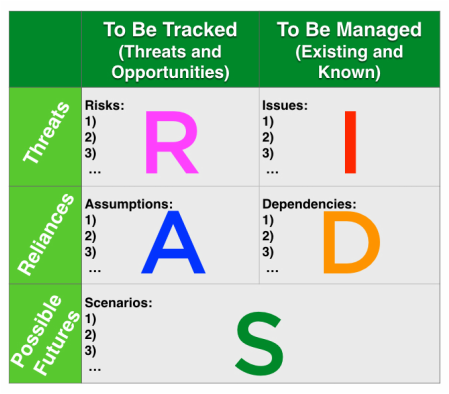

We cannot truly plan, because we do not understand the future–but this is not necessarily bad news. We could plan while bearing in mind such limitations. It just takes guts. - Nassim Nicholas Taleb (essayist, scholar, statistician, former trader, and risk analyst as well as author of The Black Swan) An entrepreneur assumes the risk and is dedicated and committed to the success of whatever he or she undertakes. - Victor Kiam (American entrepreneur and TV spokesman for Remington 1926-2001) In a start-up company, you basically throw out all assumptions every three weeks. - William Lyon Phelps (Yale professor, author and speaker 1865-1943) A RAID log or chart is a project management tool to document and track the risks, assumptions, issues and major dependencies inherent in every undertaking. It serves at least four functions: It puts all of these identified items in one place so that they can be reviewed and incorporated into other relevant plans and documents. It provides an overview which facilitates both updating as well as inclusion of new items that were either missed or have just arisen. And fourthly, it provides a starting place for efforts to examine these RAID items with a eye towards mitigation, the development of contingency plans, and the establishment of triggering signals. This is especially important for those items that could have a high impact, while taking into account their probability and timing. Each of these items i.e. risks, assumptions, issues and major dependencies, tend to be considered as a single item or event (i.e. a competitor is expected to launch their product first, the financing will close this quarter, the production is delayed, or the focus group requires a prototype). I recommend adding an additional category to the RAID log, that of scenarios, which better incorporate a series of interrelated events, hence the RAIDS log. A typical scenario may take a number of paths and incorporate the other items of the RAID log. A typical scenario might be a steep rise in the US-Canadian exchange rate which would effect financing, expenditures and revenue, and whether that would be a long or short-term event to be considered. A thorough process to initially identify, as well as periodically review and amend a project’s RAIDS log is a critical first step. Outlined below are definitions and commentary on these five categories. Some redundancy in a RAIDS log is acceptable, as the problems that can arise from omissions are far greater than managing a little redundancy. Risks: Risks are events that may occur and if they do they are likely to have a negative impact on the business. Every risk should be assigned an impact level, a probability of occurring, a timeframe, and one or more leading indicators or trigger signals. Having a competitor launch a similar product before you is a risk as it hasn’t occurred yet. The impact would be high, the probability might be between 25-50%, the timeframe could be within the next 6-9 months, and detectable triggers might include press releases, increased ad spending, hiring additional sales staff, and placing large orders to key component suppliers. Assumptions: Assumptions are items that are accepted as certain or true, but lack the evidence to make them facts. Assumptions serve to speed up and simplify planning activities by providing data points that would either be time consuming or expensive to research, or perhaps are currently unknown. The problem with assumptions, is that too frequently they are subsequently found to be untrue. This can result in significant unfavourable impacts. In effect, incorrect assumptions become risks and issues! To minimize this problem, four steps should be taken: First, best efforts should be made to identify all of the underlying assumptions in a plan. This can be more difficult than identifying risks, as there is often a fine line between what is perceived as a fact and what is indeed an assumption. Second, assumptions should be assigned an accuracy level (high-medium-low) and the resulting range of impacts accessed. Third, those assumptions, that if not accurate, could have a major impact, should be recategorized and managed as risks to ensure they receive proper attention. Fourth, those remaining assumptions should be further researched or tested with the time, effort and cost expended being relative to their potential inaccuracy and negative impact. Assuming that 10% of your targeted potential customers will purchase your product in Year 1 will drive your manufacturing, inventory, staffing, and of course financials. If it’s more likely between 6-12%, that's a two-fold swing in every aspect. Recategorizing this assumption as the risks of too few sales and potential too many sales orders, might lead you to a phased launch, identifying contract manufactures who could come on line quickly, or a stocking of the upper estimate of just the critical, long lead-time components. If left as an lower accuracy assumption, market research in the form of focus groups or field trials could be considered to strengthen it. Building a financial model is a valuable exercise on many levels. Not only does it provide a guide as to the estimated revenues, costs including development costs and profits, it also encapsulates the overall plan and the majority of the assumptions. A financial model incorporates a lot of timing items including the product launch and sales growth rates. It also incorporates many resource issues including cash flow, staffing, inventory build up and capital requirements. Finally, it incorporates many sales assumptions including market size and penetration, pricing, volumes and the required marketing efforts. While building a financial model, many of the underlying assumptions will become apparent. They can then be tracked, challenged and tested as required. Issues:

Issues are current problems that need to be addressed. Hopefully, most of them arise from previously identified risks for which some mitigation or contingency planning has already been done. Each issue should be assigned an impact, which is the primary means of prioritizing the urgency as well as the effort (effectively time and cost) that should be brought to bear. If unit or dollar sales are not meeting target, increasing marketing and sales efforts, altering production outputs, or changing the pricing might be considered. Dependencies: Most commonly, a task is dependent on a preceding task if it can not be started until the predecessor has been completed (also termed a start-to-finish relationship). A product can not be delivered until it has been both sold and produced. The core tools and associated documentation of project management are Gantt charts, and PERT or network diagrams. A key aspect of these tools is the establishment and tracking of task dependencies. Specifically highlighting the major dependencies as well as the critical path (that sequence of dependent tasks that determine the shortest possible time required to complete the project), ensures that efforts are properly prioritized and resourced. Building and fully testing a working prototype so that it can be available for demonstrating as part of the product announcement at a major industry conference is an example of a critical dependency. As a result, this would be a top priority for the development team. Scenarios: A scenario is a postulated sequence of dependent events that incorporates a variety of assumptions (or variables). Scenario planning usually involves the consideration of a key question (often a high impact risk) and a relevant timeframe. From there, a list of driving forces are identified (STEEPLED external analysis is a good starting point), followed by a list of the resulting uncertainties. These are examined and a number of plausible scenarios are developed from which sets of implications, paths and risks are ultimately derived. In effect, each scenario is a story about how the project might unfold. Exploring a variety of scenarios and some possible branches of any given scenario can identify important downstream risks that may be missed by simply listing or brainstorming risks one by one. Disaster scenarios including fires, computer hacks and major spills are examples commonly explored by firms so that appropriate and detailed emergency action plans can be prepared. A scenario to be explored in a new product development project could be the limited availability of a key component as a result of supplier problems. This would raise questions as to whether a second source supplier should be qualified, or whether a strategic inventory of the component should be secured in advance. - - - Having your project team develop a detailed list of items coinciding with the five components of the RAIDS log, i.e. the risks, assumptions, issues, dependencies and scenarios, as well as associated risk mitigation strategies and contingencies should significantly reduce surprises, headaches, so called “fire fighting,” and improve the overall success rate of your project. For more information on prioritizing and mitigating risks see RISK: Identification, Assessment and Contingency Planning. |

AuthorDuncan Jones Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed