|

“All men make mistakes, but a good man yields when he knows his course is wrong, and repairs the evil. The only crime is pride.” Sophocles, Antigone

“So many people live within unhappy circumstances and yet will not take the initiative to change their situation because they are conditioned to a life of security, conformity, and conservatism, all of which may appear to give one peace of mind, but in reality nothing is more dangerous to the adventurous spirit within a man than a secure future. The very basic core of a man’s living spirit is his passion for adventure. The joy of life comes from our encounters with new experiences, and hence there is no greater joy than to have an endlessly changing horizon, for each day to have a new and different sun.” Jon Krakauer, Into the Wild I have been thinking about the challenges of effective portfolio management and recently attended a related webinar by Don Creswell (www.smartorg.com). As he points out, portfolio management requires decisions involving issues of economics (strategy and priorities) and resources (budget, staffing), as well as executing on and tracking the process (timelines and milestones). Done well, portfolio management aligns the activities of the company with what is best for the company technically, commercially, financially and operationally in both the short-term and longer-term. The biggest impediment to good portfolio management is found at the intersection of the inherent self-interests of individual project leaders and the company’s reward system. This is especially apparent when trying to terminate projects, but also arises in the selection and resourcing projects. As Creswell points out, it’s rare that a project leader and the team accepts a termination decision as the result of a fair and accurate analysis and even rarer that they come to the same conclusion themselves. The underlying question haunting and holding back these project leaders and team members is, “What will I do now?” and frequently companies don’t provide sufficient answers. Michael LeBoeuf’s insights in his 1985 book the “Greatest Management Principle in the World” include: “What gets rewarded gets done” and “If things are not getting done, ask yourself - What is being rewarded?” If the “reward” for terminating a large project, is the risk of being declared excess and being laid off, or being seen as a failure and having your reputation as well as your leadership position jeopardized, then it’s little wonder that there is resistance to cancelling projects. We have all witnessed that most projects once started take on a life of their own. Indeed, honest evaluations and reassigning of resources from the weakest projects to the strongest and most strategic ones is rare. Weaker projects maintain an incredible survival inertia even when senior management have demanded termination. This, like the majority of business problems, is a people problem and Michael LeBoeuf directs us to the solution. For a portfolio management system to thrive, the company’s culture must embrace failure, reward actions that are in the company’s best interest, and have a strong retention process. I won’t go into embracing failure, except to say that failure needs to be celebrated and used as a learning tool in organizations. This was the subject of a previous blog, “‘It’s time to re-evaluate failure’ - Implications for School and Work.” The corporate reward system has to likewise recognize project failures, not from poor management, poor effort or avoidable errors, but from solid work on a risky endeavour that after some experimentation is deemed unfeasible. After all with no risk-taking there is little likelihood of significant improvements and returns. Salary, bonuses, promotions and even pats on the back need to thus be aligned with strong efforts and learning, and not just success, or very soon only incremental projects will be undertaken. Significant efforts and costs are required to find, hire, train, compensate and supervise employees. Once hired, it is in a company’s interest to ensure that employees are fully engaged, and that they receive the additional training and support (budget, staff, information) to achieve their objectives. In the case of project leaders and teams who are impacted by a project termination, they should be allowed to select, be recruited to or be assigned to another ongoing project to which they can contribute, or even be given time to develop a new project proposal. Knowing that they will be guaranteed reassignment removes much of the fear and encourages the desired behaviours. In one progressive instance, three of the project leaders including myself were sent to see an Industrial psychologist near the completion of a major project. We were then each given a new assignment that was the best fit for the company and our career progression based on this evaluation. Embracing failure, rewarding pro-company behaviours and supporting your existing employees can go a long way to reducing the apprehensions project leaders and teams have about their own security and reputation in the face of risky projects. This is the foundation of an effective portfolio management system that is able to undertake risky projects, re-allocate resources as required and terminate projects in the face of better alternatives or a shifting competitive and market landscape.

0 Comments

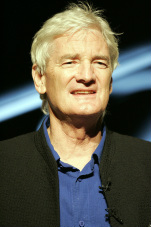

In today’s Globe and Mail newspaper (15/Aug/2014), James Dyson of vacuum and fan fame wrote an excellent article describing how “failure just is part of the process” and that developing his cyclonic vacuum took 15 years and 5,127 failures! He goes on to say “that if you fail once, you’re one step closer to success” and that failure should be “encouraged, accepted, even sought after. Because it’s failure that drives invention forward.” See /http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/careers/leadership-lab/yes-its-ok-it-took-me-5127-attempts-to-make-a-bagless-vaccuum/article19992476/ SOURCE: Eva Rinaldi from Sydney Australia Indeed James Dyson is not alone as a successful inventor and entrepreneur who embraces failure. Other famous people include Thomas Edison and his light bulb, The Wright brothers and human flight, Edwin Land and instant photography, Steve Jobs and the Apple computer, and Elon Musk and the Tesla electric car as well as SpaceX private spaceflight, to name a few. The nature of invention and innovation is experimentation and with experimentation comes frequent failure. If you knew exactly what to do to succeed, it’s likely someone would have done it already. Through failure, and especially documenting and reviewing it, comes learning and such learning leads to new ideas and breakthroughs. So why is failure so shun in all but the most progressive (and in many cases successful) schools and workplaces? Why is failure attributed to stupidity and waste and not experiential learning and eventual success which are so highly touted? Why are failures hidden or swept under the carpet instead of celebrated and shared so that the learnings can be also be shared (as again they are at some progressive companies)? In the majority of the high school and undergraduate university education systems, the achievement of high marks alone has come to dominate regardless of the underlying learning and ability to apply it. Frequent testing and marking is used as a hammer to motivate students to keep up, as marks are the primary screen for advancement. Much of it becomes rote learning, simply, easily and unambiguously assessed by multiple choice questions. Since everything counts, there is little room for failure nor productive feedback and I might add the kind of experiential learning that is so sought after and important to innovation. Likewise In the majority of companies, a stumble free and failure free career path is what drives promotion and its spoils - higher salary and status. The dominate model is to keep your head down and not take any chances. Again without taking calculated risks there will be little chance of the kinds of rewards that Dyson, Edison, Orville and Wilbur, Edwin, Steve and Elon have brought to their respective firms and society as a whole. We have also all come to learn the risks firms take and the often serious consequences when not continuing to innovate in the face of global competition. So what can and should be done? A few ideas come to mind: In the educational systems, more testing for individual feedback as opposed to assessment should be done. I recently completed a massive open online course (MOOC) that incorporated numerous problem sets and given that I was taking it for my own interest, these served only as effective feedback that reinforced my learning. Creative, experiential and experimental activities should be encouraged, one of my favourite being science fairs. The assessments should cover effort, creative thinking, response to mentoring, and learning as much as end results. I once took a lab course in analytical chemistry in which instead of performing prescribed experiments, we were allowed to experiment on our own. We got a good feel for capabilities of the sophisticated equipment by tested a variety of samples and changing the various settings sequentially and observing the effects. Pass/Fail/Retry types of hurdles should also be incorporated, like a driving test. Essays and projects could be submitted, receive comments and constructive criticism, and be then resubmitted until they achieve an acceptable standard. In the workplace, a culture change is required. First off, innovation needs to be moved to the forefront of most organizations. Coincident with this, best efforts (i.e. well thought out and executed plans) should be celebrated in addition to only success. As Michael LeBoeuf points out in one of my favourite books, “The Greatest Management Principle in the World” (1985): “What gets rewarded gets done.” He goes on to propose that if you want risk-taking, you need to reward it with recognition. This in turn will drive what Chris Argyris coined double loop learning (1974) in which not only are a firm’s experimental and even general business techniques and tactics reviewed and improved upon, but so are the underlying assumptions. Such a process addresses effectiveness as well as efficiencies leading to better solutions and outcomes. In one early-stage company I worked in, the two engineers devised a friendly competition between themselves to come up with the best clutch system for a power wheelchair. After a first round, they shared their solutions and then embarked on a second independent round. We eventually filed a patent (US 6209670 B1) and incorporated the “winning” design. Failure should be embraced and celebrated, especially by individuals intent on fostering learning and innovation. This will require some courageous and creative actions (some of which may even fail!). “I've missed more than 9000 shots in my career. I've lost almost 300 games. 26 times, I've been trusted to take the game winning shot and missed. I've failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.” Michael Jordan, professional NBA basketball player, entrepreneur and 5 time MVP. "Lack of scientific R&D funding will leave Canada in the dust" - A role for academic collaboration?8/15/2014 In today's Globe and Mail newspaper (1/Aug/2014), economist Todd Hirsh wrote an article with the aforementioned title. See https://secure.globeadvisor.com/servlet/ArticleNews/story/gam/20140801/RBELHIRSCH#

In his article, he points out that R&D is critical as it drives innovation, which in turn is important for economic growth. In addition, he references OECD data indicating that Canada lags most other wealthy nations on R&D spending at 1.74% of GDP. Much of this R&D is of course done at institutions of higher learning. Perhaps most importantly, Canadian businesses only provide 8.1% of these university/college/ hospital research funding or $343/ person. This got me thinking as to why in general Canadian firms don't carry out much (enough?) research and especially why they don't collaborate with and fund university/college/ hospital research. The three things that hold back research efforts are fears relating to: the cost, the risk, and the potential return. Cost involves both management time and focus, and of course money. The risk or probability of success is a function of not only the inherent risk based on the novelty of the task or goal but also on the technical skills, the management skills and the experience of the team. Finally, the return or resulting value depends on the customer, market and competition. These fears are real but are also manageable (More on this in a future blog). It also should not be forgotten that doing nothing, that is staying with the status quo, also can bring significant costs, risks and negatively impact returns (think Blackberry, Blockbuster, Kodak to name just a few). Collaborating on R&D projects with institutions of higher learning can lower costs through leveraging government support, obtaining access to specialized equipment, and in some cases employing student labour. Collaborating with academics can also provide one with insights into the market and especially competitive activities. But most importantly, such collaborations give a firm access to unique academic expertise, creativity, and research skills and methodologies that can significantly increase the probability of commercial success. So why is there not more industry-academia collaboration? I believe this is a result of a fourth fear: dealing with academics and academic institutions. This fear is also manageable and is achieved through understanding, communication, and managing expectations. This fear relates to the academic culture or style, academic time and focus, and administration as follows: First as far as culture is concerned, academia is founded on the security of academic freedom which encourages risk-taking and speaking one's mind from which we all (i.e. society) benefit. As a result, academics are in effect independent operators with no boss or supervisor and a guaranteed salary. Academics in the sciences and technology, especially the best, are also well-funded to carry out their research by a variety of government programs, charitable foundations and in a some cases industrial partners often concurrently. This significantly shifts their work motivation away from one of financial need towards one of interest and challenge. Hence academics need to be courted with interesting projects and open, potentially long-term collaborations as opposed to be pressed as is often the case in business customer to supplier, and boss to subordinate relations. On the matter of academic time and focus, as already mentioned academics tend to have a number of projects on the go, in addition to graduate student responsibilities (the manpower behind much of the research) and of course teaching. These activities can not be just put aside, in order to focus solely on your project. Hence timelines and access to academics must be prudently negotiated to ensure their are no disappointments or surprises. Finally, academic administration can at times seem burdensome. In addition to academic freedom issues especially as they relate to publication (remember the academic mantra of "Publish or Perish), issues of intellectual property ownership, royalties, using students, and funding support for departmental overheads, among other things, always arise. By understanding the institution's role, goals, policies and limits, much of which can be outlined while working with each institution's technology transfer (or industrial liaison) office, while conveying your business needs, will result in smooth and fruitful negotiations. Given that we have some of the best academic research and researchers in the world (by a variety of measures), Canadian companies need to learn to better manage and in doing so overcome their fears of cost, risk, potential return and especially academics. By leveraging this local academic talent and collaborating on R&D projects, incredible breakthrough innovations can arise. Duncan Jones, principal of www.Hexagon-Innovating.com, works for you and your team to facilitate and optimize your innovation efforts. He has experience establishing and managing industry-academic partnerships, having worked on both sides of these partnerships in- and out-licensing technologies, in addition to funding and supporting academic founders when he was an early-stage venture capitalist. |

AuthorDuncan Jones Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed